An international collaboration between researchers from the University of Oxford, Thailand, Switzerland and the USA has revealed a previously unrecognized link between metabolic stress in the nucleus and a cell’s ability to make proteins.

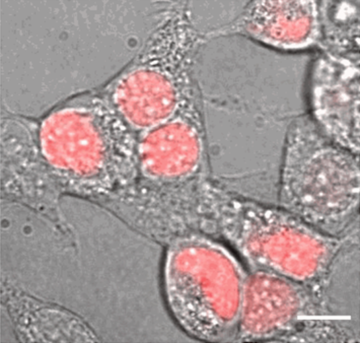

The NCBP1 protein with nuclear stress-sensing function, as discovered in this study, in the cell nucleus (pink) as shown by live fluorescence imaging.

The study from the Aye group at Oxford Chemistry demonstrates how localized accumulation (or build-up) of lipid-derived metabolites can have an impact across the cell, ultimately slowing protein synthesis. You can read the full study in Nature Chemical Biology.

The team developed a method that generates a small stressor metabolite to different positions across the cell and measures the effect of this molecule on the cell’s ability to convert messenger RNA into proteins (a process known as translation).

Once the team had pinpointed the nucleus as the weak point for this process, they investigated the mechanism by which the stressor molecule suppressed translation. This involved identifying the protein within the nucleus that senses the stressor, and showing that this sensing event leads to a change in RNA splicing. This goes on to produce an unusual form of a specific protein that then inhibits translation.

The group’s work is the first study that links nuclear stress buildup to a decrease in translation. It also identifies one of the earliest known gain-of-function mechanisms triggered by small-molecule cellular stressors – that is, a process in which a single chemical modification on a fraction of the specific upstream protein activates new downstream cellular functions.

Prof Yimon Aye says:

Our tools that can generate controlled dosages of these small reactive stressor molecules with absolute timing and location are beginning to tease apart nuanced regulatory mechanisms of the cell that are otherwise very challenging to interrogate.

Read more in Nature Chemical Biology.