Our history

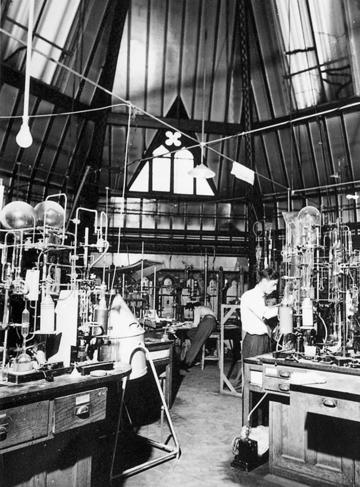

Dr Staveley's Laboratory (the Abbot's Kitchen) in 1945

Chemistry was first recognised as a separate discipline at Oxford in 1860 with the building of a laboratory attached to the Museum of Natural History. The laboratory, a small octagonal structure, was built in the Victorian Gothic style and replicated the architecture of the Abbot’s Kitchen at Glastonbury Abbey. One of the first purpose-built chemistry laboratories anywhere, it is still referred to as the Abbot's Kitchen today.

The Abbot's Kitchen was extended in 1878 and again in 1957 to become the main Inorganic Chemistry Laboratory. Organic Chemistry was housed in the Dyson Perrins Laboratory, built in 1916, and the Physical Chemistry Laboratory (later to become the Physical and Theoretical Chemistry Laboratory), was built in 1941. In 2004 HM the Queen opened the new Chemistry Research Laboratory, and 2018 saw the completion of a new purpose-built facility for undergraduate teaching, the Chemistry Teaching Laboratory.

Oxford Chemistry laboratories

Following the expansion of 1957, the Inorganic Chemistry Laboratory (ICL) went on to comprise of five floors of laboratories, workshops, offices and seminar rooms as well as occupying for a time the whole of 9 Parks Road (the Chemical Crystallography Laboratory) and a substantial portion of the New Chemistry Laboratory (the Old Pharmacology building) in South Parks Road. It is the biggest school of inorganic chemistry in the UK and one of the biggest in the world.

The laboratory has had a remarkable series of professors associated with it. The early professors of chemistry included William Odling (1855 to 1912), who had some claims to the formulation of the Periodic Table, and Frederick Soddy (1919 to 1936) who was awarded the Nobel Prize for his discovery with Rutherford of the radiochemical series. He was followed by another Nobel Prize winner for chemical kinetics, Cyril Norman Hinshelwood (1937 to 1964), who was professor of physical and inorganic chemistry.

The first statutory professor of Inorganic Chemistry was J S Anderson (1963 to 1975), who was succeeded by John B Goodenough (1975 to 1988), now a Nobel Laureate for his role in the development of the lithium-ion battery. Malcolm Green, renowned for his imaginative work in organometallic chemistry, succeeded Goodenough in 1988, followed by Professor Peter Edwards in 2003. The current Head of Inorganic Chemistry is Professor John McGrady.

Other notable chemists who worked in the laboratory or were closely associated with it were Nevil Sidgwick, the author of a monumental work on inorganic chemistry, Jack Linnett (later vice-chancellor of Cambridge), William Hume-Rothery, who founded the Department of Metallurgy (which is now the Department of Materials), and Dorothy Crowfoot Hodgkin, who was awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1964 for her determinations by X-ray techniques of the structures of important biochemical substances. Hodgkin was, and remains to date, the only British woman ever to have been awarded a Nobel Prize in the sciences. One of her students was Margaret Thatcher (nee Roberts), who went on to serve as the first woman Prime Minister from 1979 to 1990.

Blue plaques on the front of the Inorganic Chemistry Laboratory mark some of the greatest achievements of twentieth century chemistry: the identification of the cathode material that enabled the development of the lithium-ion battery, the creation of the Glucose Sensor, and the work of Dorothy Hodgkin.

Opened in 1916, the Dyson Perrins Laboratory (DP) was named in honour of CW Dyson Perrins, who made a massive benefaction derived from Lea & Perrins Worcester sauce. The DP was the base of one of the world’s leading Departments of Organic Chemistry until 2003. When the laboratory was handed over to other university use in 2004, it was declared a Historic Chemical Landmark by the Royal Society of Chemistry.

Some of the most illustrious chemists of the twentieth century were based in the Dyson Perrins Laboratory and include:

William Henry Perkin, Jr., FRS (1860–1929), who was known for his work on natural organic compounds. He was the eldest son of Sir William Henry Perkin who had founded the aniline dye industry.

Sir Robert Robinson, (1886–1975), who won the Nobel Prize in 1947 for his research on plant chemicals anthocyanins and alkaloids. He was also known for inventing the benzene symbol and the use of the curly arrow to represent electron movement.

Ewart Jones (1911 – 2002), known for his work on the chemistry of natural products including vitamins and steroids.

In 2008 John Jones with the help of Part II students Rachel Curtis, Catherine Leith and Joshua Nall published a book entitled The Dyson Perrins Laboratory and Oxford Organic Chemistry from 1916-2004. (ISBN 978-0-9512569-4-7).

The Physical Chemistry Laboratory was built in 1941 and at that time also housed the inorganic chemistry laboratory. It replaced the Balliol-Trinity Laboratories. The east wing of the building was completed in 1959 and Inorganic Chemistry, already in its own building on South Parks Road, then became a separate department in 1961. In 1972, the Department of Theoretical Chemistry was established in a house on South Parks Road, and in 1994, the amalgamation of the physical and theoretical chemistry departments took place. This was followed shortly by the theoretical group moving into the PTCL annexe in 1995.

As part of the 50th Anniversary of the PTCL in 1991 a book was produced detailing the history of the laboratory. The content of these pages is based on that book. In the first section are some facts and figures from published reports and members of the laboratory collated by Richard Barrow, whilst the second part is a personal account by John Danby. The original text was written in 1991, but was updated by Professor Sir John Rowlinson to include activity over the period 1991-2001.

The PTCL has been home to many illustrious chemists. At the time of its construction the Dr Lee’s Professor was Sir Cyril Hinshelwood, whose work with Nicolay Semenov on the mechanisms of chemical reactions led to the award of a Nobel Prize in 1956. Hinshelwood’s successor, Sir Rex Richards, distinguished for his work on nuclear magnetic resonance, would later become University Vice-Chancellor. Kineticist Sir (later Lord) Frederick Dainton then held the post until John Rowlinson took over the reins in 1974.

Since Professor Rowlinson, the Dr Lee’s Chair has been held by Professors John Simons (1993), and Jacob Klein (2000). The current Dr Lee’s Professor, Dame Carol Robinson, is renowned for her pioneering use of protein mass spectrometry. She also has the distinction of having been the first female Professor of Chemistry at both Oxford and Cambridge universities. The current Head of Physical and Theoretical Chemistry is Professor Grant Ritchie.

The Chemistry Research Laboratory was opened by Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II in 2004. The laboratory has five floors covering approximately 17,000 sq. m of lab and office space and cost 60 million GBP to construct. It was partially funded by an innovative IP deal which gave the investors (IP Group) a share of the profits from commercialization of research and spinout companies over 15 years.

The Chemistry Teaching Laboratory, opened in 2018, is the Department's newest building. Designed by architects Francis-Jones Morehen Thorp, the state-of-the-art teaching labs provide a dedicated space for undergraduates in a fully-accessible building. The two main labs are spread over two floors, each with space for up to 100 students. The labs house over £2M worth of equipment for undergraduate use, including a multinuclear NMR spectrometer, gas chromatographs, an HPLC set up for analysing chiral compounds, a TLC-mass spec, ICP/MS, and bench-top NMR spectometers. The new building and equipment have helped to enable Oxford Chemistry undergraduates to enjoy a fully-integrated practical course and the Director of the Teaching Laboratory is Dr Malcolm Stewart.